Bergerac’s origins lie in the existence of a castle, built at the end of the 11th century on the banks of the Dordogne, which attracted a population previously scattered across the plain.

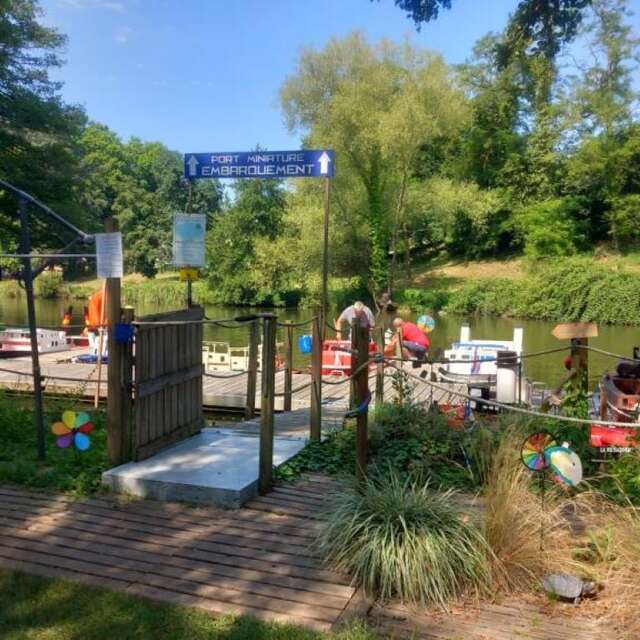

The village grew to become a stopover for travelers, pilgrims and merchants a century later. The construction of the church of Saint Jacques and a hospital confirmed this expansion. In the 13th century, the development of viticulture and the growth of trade led to the construction of a bridge over the Dordogne. Involved in the municipal movement, the town acquired freedoms and franchises, which were to make its fortune, as it could now export its wines. The agglomeration expanded and spilled over into the suburbs, where convents of the mendicant order were established. Cereal crops reached the city gates, while vines dominated the hillsides from this period onwards.

In the middle of the 14th century, the city was caught up in the Franco-English conflict, in which it maintained its position as a free and independent city through its diplomatic strategy. Nevertheless, it lost half its tax-paying population. After a demographic recovery, the municipal authorities restructured urban life and regulated public hygiene. With peace, commercial prosperity returned, but the population fell in love with Calvinist ideas. The peaceful trading town became a powerful Protestant stronghold, with convents and churches destroyed.

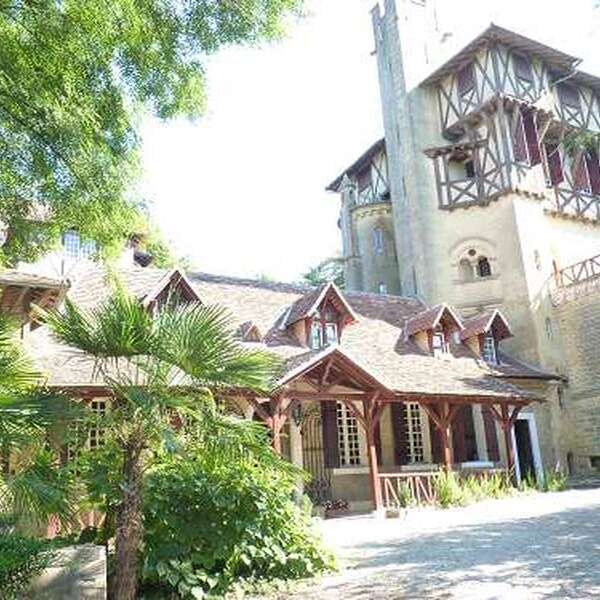

Despite the Wars of Religion, the population lived a peaceful and wealthy existence, sheltered by its defenses. The arrival of the printing industry gave Bergerac, then known as “Little Geneva”, a new lease of life. The new opulence was expressed in fine architectural schemes, including the Hôtel des Peyrarède built in 1604. This brilliant period of independence came to an end with Louis XIII’s reconquest of the towns. Opening their gates to the royal armies, the people of Bergerac organized a solemn entry for the sovereign. He had the fortifications dismantled and a citadel built to the east of the town. He installed an infantry regiment, set up a dedicated municipality and left a mission of Récollet fathers. Reformed and Catholics coexisted as best they could until the new persecutions and dragonnades at the end of the century, which emptied Bergerac of its lifeblood. Depopulated, the town became a land of mission, where numerous congregations quickly mastered the institutions and built up substantial land holdings.

In the 18th century, Bergerac maintained its role as a major regional market, but failed to regain its former dynamism. Although situated on a major communications axis, the town remained landlocked in the 19th century.

Thanks to its late arrival in the industrial age, Bergerac owes its high-quality urban development to a well-preserved environment.

Bergerac

Bergerac